Historical Flashback: The Great Sea Islands Hurricane of 1893

A monster storm that left an impact on culture, race, politics and the economy far into the next century.

When fall creeps into the South, the days wane, and the coastal breezes begin to blow, the locals know what’s coming: there are monsters storming in from the Atlantic and it’s time to prepare.

Hurricane season can be a brutal time for those living in South Carolina, Georgia, and across the South, but in the yesteryears before scientific advancements and modern meteorology, the storms of the Atlantic often took coastal residents by surprise, leaving behind unimaginable death and destruction.

One monster storm left an impact that reached into the next century.

When a South Carolinian thinks of the worst hurricanes in Palmetto State history, Hugo, Andrew, and Gracie often come to mind, but no S.C. storm rivals the Sea Island Hurricane of 1893 in terms of deaths, devastation, and the lasting impact it left behind.

No warning, no way to higher ground

While the science of meteorology dates back millennia, significant progress in weather forecasting did not come until the 18th Century. During earlier eras, hurricanes were often referred to and named by the year, or the city and area where they made landfall.

In 1849, meteorologist Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., began plotting daily weather maps based on telegraphic reports, and in 1869 Cleveland Abbe at the Cincinnati Observatory began to provide regular weather forecasts using data received telegraphically.

In 1953, American scientists began assigning names to Atlantic hurricanes and during that same decade, armed with better weather data and improved computer capabilities, began building the first hurricane forecasting models. The science of forecasting took another leap forward during the satellite era of the 1960s.

Prior to these advances, early Southeast residents relied on their natural instincts or folk wisdom, noting the way birds and animals behaved, or a change in the sun or the breezes. Native Americans and early settlers could sometimes tell when a storm was approaching – but perhaps with only a day or two of warning and no real way to get to high ground in time.

The America that saw the impact of the Sea Islands Hurricane of 1893 had the scientific advantages of telegraph and early telephones to help spread the word of approaching storms, but news of disaster often failed to reach the most isolated, rural and self-sufficient coastal residents.

(Damage from the 1893 storm on Bay Street in Beaufort, S.C.)

The deadliest hurricane in South Carolina history

The late 1800s go down as one of the worst periods of back-to-back, killer storms in recorded American history. For example, the “Georgia/South Carolina Hurricane” arrived at high tide in August of 1881, catching coastal residents by surprise and killing 700 people. Several hurricanes in the 1880s and 1890s later grazed or impacted the Southeast area.

But these storms were just a warmup for the Sea Islands Hurricane, which struck just south of Tybee Island and Savannah, Georgia, on Aug. 27, 1893, devastated the coastal regions and barrier islands of Georgia and South Carolina, and today is considered the fourth deadliest hurricane in U.S. history.

On Aug. 25 of that year, reports began trickling in from seafarers and Florida areas of a massive storm approaching the area. Word slowly spread to some, by telegraph, word of mouth, and in rare cases by the new telephone system, but many isolated, rural area residents did not receive the warning.

“Home to more than 30,000 African Americans who farmed, worked in rice fields, and plied nearby waters for fish, oysters, shrimp, and crabs, the Sea Islands were accessible only by boat,” recorded the New Georgia Encyclopedia, adding “Their remote location allowed for the preservation of the unique Gullah and Geechee culture, but limited communication with the mainland—a fact that would carry dire consequences for residents unprepared for the coming storm.”

The Sea Islands Hurricane, packing estimated 121 mph winds and a 16-foot storm surge (a Category 3 by today’s scales), struck the Southeast coastlines in an explosive blitzkrieg of saltwater and wind, completely submerging many sea islands and coastal towns before moving inland and up the Atlantic seaboard.

During the height of the storm, most of the Beaufort-area sea islands and Sullivan’s Island were completely submerged, and many Charleston streets were under as much as ten feet of water, recorded historians and newspapers of the day.

It took a day or two for news of the actual impact on the low-lying sea islands to reach the mainland. When the waters receded, survivors and relief workers found drowning victims everywhere, from beaches to tree limbs and roof tops.

“Bodies of drowning victims washed up on beaches and were found strewn throughout marshes and in creeks and streams throughout the Georgia and South Carolina Lowcountry,” records New Georgia Encyclopedia. “Nearly every building on the Sea Islands was reported to have been destroyed.

“The rail lines from Savannah to Tybee were uprooted and mangled. The Savannah Press described structures in a state of utter disrepair, with ‘roofs of tin peeled off like paper strips.’ Ships were wrecked at Savannah, and a schooner washed ashore on Jekyll Island.”

The storm left at least 2,000 people dead and 30,000 homeless, with the vast majority being Black and Gullah residents, according to New Georgia and other historical records. Many of those victims were in the sea islands of Beaufort, and islands like St. Helena, Hilton Head and Daufuskie were devastated.

The number of fatalities places this storm on the level with Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and some researchers believe this storm was of equal intensity to the 1900 Galveston, Texas, hurricane, claims a University of Rhode Island report, “Hurricanes: Science and Society,” although the Galveston storm killed many more people.

But S.C. historians say the Sea Island storm deaths were likely underreported, making it far more deadly than officially estimated. Many of those who drowned, or went missing, were rural Blacks who had little or no means of reporting casualties. Some historian estimates place the death toll as closer to 5,000, but it could be even higher.

An Oct. 2, 2024, article by Andrea Thompson in Scientific American now suggests that death rates for surviving hurricane victims remain higher than average long after the storms, with storm victims often dying months or years later from exposure to mold contamination, pollution and even extreme heat- or stress-related illnesses.

This storm was historically significant for more than just its damages and death tool. It would prove to be the first major hurricane relief operation ever conducted by the newly formed American Red Cross. It would also prove to be a storm that left societal and historical impacts into the next century.

(Red Cross founder Clara Barton not long after the 1893 disaster.)

The long-term impact of the Sea Islands Hurricane

The Red Cross did not arrive until Oct. 1. They had a challenge ahead of them.

Relief workers arrived to find the city of Beaufort in rubble and ruin, with more than 20,000 surviving refugees from the city, surrounding towns and farms, and the nearby Sea Island areas filling the streets looking for food, supplies and shelter, recorded Red Cross founder, nurse Clara Barton.

At several points early in the disaster, Barton and her Red Cross associates even handed out food and supplies by hand from boats to stranded survivors.

Relief centers were established, food and other supplies were rationed, ditches dug to drain the flooded islands, homes rebuilt, and later, crops replanted and livestock replaced.

It took a ten-month relief effort before most of those displaced victims could return to rebuilt homes with adequate food supplies, but economic recovery would take decades. Damages were estimated at a conservative $1 million (likely due to the rural nature of the area, as opposed to more costly damages in a city), which would equal more than $35 million today.

Forests, buildings, bridges, railroads, ports and other infrastructure were demolished up and down the coast. People who relied on agriculture for survival found their livelihoods eradicated. But infrastructure could be rebuilt, and crops replaced; some victims saw the end of a way of life.

“Economic turmoil plagued Beaufort for half a century after the hurricane,” cited the University of Rhode Island report.

The 1893 storm, combined with the damage by previous storms, virtually wiped out and eventually ended Beaufort’s and South Carolina’s phosphate mining and indigo industries, cite numerous historical sources. Coastal damages and storm erosion, combined with the earlier loss of free, forced slave labor after the end of the Civil War, ultimately contributed to the end of the South Carolina’s rice growing culture and pronounced the death of many rice plantations.

Five years later, a Category 4 storm struck Brunswick, Ga., but the Sea Islands Hurricane remains the deadliest storm ever to make landfall in the Peach State and S.C.

Agricultural, cultural impacts

Rice was first planted not long after Charles Towne (modern-day Charleston, S.C.) was founded in 1670, and wealthy rice planters were a powerful, dominant economic and political force by the early 19th Century in coastal S.C.

A historical, record-breaking series of hurricanes in the 1800s and early 1900s severely impacted agriculture in S.C. and Georgia, particularly the rice planters. Major storms struck from Georgia to North Carolina in 1804, 1811, 1813, 1814, and 1815, 1822,1893 (twice), 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, 1904 1906, 1908 (twice), 1910 and 1911.

These storms killed enslaved laborers, destroyed rice impoundments and infrastructure, and flooded fields with saltwater.

The outcome of the Civil War brought the end of free and cheap labor for the rice plantations, and without slave labor to rebuild, these latter hurricanes “dealt a final blow to a decaying agricultural economy that had once depended on slavery to survive,” wrote Coastal Heritage Magazine (Volume 13, No. 1, Summer 1998, edited by John H. Tibbetts). “Giant storms put the last nail in the coffin of rice plantations along the South Carolina and Georgia coast and helped to usher in a new presence along the coast—wealthy Northerners who bought bankrupt plantations and turned them into hunting preserves.”

The demise of the rice culture and other agribusiness also led to the creation of an independent Black culture along the coast and on the sea islands. Former slaves became small farmers, or made a living from fishing, oystering, turpentine gathering, lumbering, etc.

“Hurricanes, in fact, were a tremendous blow to the political and economic power of plantation owners,” wrote Coastal Heritage. “At the same time, many Blacks were moving toward greater independence, establishing a small-landowner class along the coast.”

Social, racial, and political impacts

The Sea Islands storm also had racial and societal impacts that both echoed problems left from pre-Civil War slavery and Reconstruction, and impacted race relations and eventually government policy moving forward.

“Racial tensions flared as white mainlanders complained that Black residents on the barrier islands, who were the hardest hit, were getting most of the assistance,” wrote New Georgia.

A paper in The Journal of Southern History, authored by Carolina Grego and titled “Black Autonomy, Red Cross Recovery, and White Backlash after the Great Sea Island Storm of 1893,” took a deep dive into those issues.

“Several historians have turned to the storm as a transformative and explanatory moment in Lowcountry history… and they have interpreted the storm as a flashpoint for memories of Reconstruction and for questions of responsibility in disaster recovery,” wrote Grego.

Grego wrote of “the white supremacist backlash against the coalition of the Red Cross and black sea islanders…,” tracking how “a uniquely independent black Lowcountry community” overcame those “who resented the persistence of black autonomy on the coast.”

Grego, a history professor at Queens University of Charlotte, noted that, at the time of the storm, S.C.’s Governor was “the infamous white supremacist and demagogue Benjamin R. Tillman,” also known as “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, who likely accepted the Red Cross’s offer of hurricane relief to shed the responsibility from his office.

Thus, it was the fledgling American Red Cross, working hand in hand with the people themselves to rebuild and recover, who spearheaded relief efforts for South Carolina hurricane victims, and not their own state or local government, which illustrated a problem in public policy that cried for reform.

In her diary, Clara Barton, wrote that it was “a great undertaking” to “feed, clothe, work, doctor and nurse 30,000 human beings for eight months, and do it all upon charity gathered as one goes along.”

For nearly a year, the Red Cross aided sea island residents until homes were rebuilt and new crops were planted and ready for harvest.

“The submerged lands were drained, 300 miles of ditches made, a million feet of lumber purchased, and homes built, fields and gardens planted with the best seed in the United States, and the work all done by the people themselves,” Barton wrote, as the Red Cross completed the mission and moved on to aid other areas in need of relief.

Historians like Grego, and modern Gullah Geechie scholars, continue to examine the storm and its relief efforts in context of the end of Reconstruction and the birth of more modern eras.

Grego recently authored Hurricane Jim Crow: How the Great Sea Island Storm of 1893 shaped the Lowcountry South, which was published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2022.

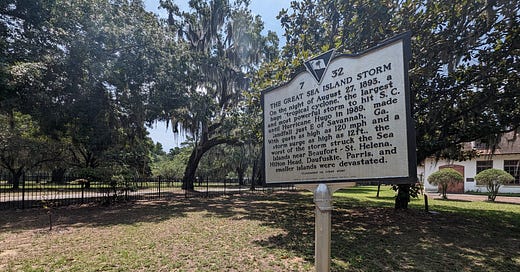

In 2008, the Beaufort County Historical Society erected a historical marker, remembering the storm and the lives lost, at the Penn Center National Historic Landmark District, located at 24 Penn Center Circle West, St. Helena Island, S.C.

Sources and links

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/storm-names.html

https://www.britannica.com/science/weather-forecasting/History-of-weather-forecasting

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/top-10-deadliest-hurricanes-in-us-history-katrina-maria-galveston/

https://www.eatstayplaybeaufort.com/the-sea-island-hurricane-of-1893-4th-deadliest-in-us-history/

https://hurricanescience.org/history/storms/pre1900s/1893/

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/1893-sea-islands-hurricane/